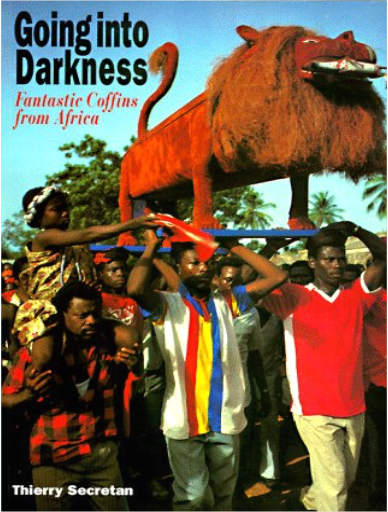

A spirited view of a somber subject, this book is a treasury of Jewish history, legend and lore. Over 200 photographs offer a look at the graven images that have traditionally decorated Jewish tombstones in Europe.  The nineteenth century seems to have been full of hysterical women—or so they were diagnosed. Where are they now? The very disease no longer exists. In this fascinating account, Andrew Scull tells the story of hysteria—an illness that disappeared not through medical endeavor, but through growing understanding and cultural change. The lurid history of hysteria makes fascinating reading. Charcot's clinics showed off flamboyantly "hysterical" patients taking on sexualized poses, and among the visiting professionals was one Sigmund Freud. Scull discusses the origins of the idea of hysteria, the development of a neurological approach by John Sydenham and others, hysteria as a fashionable condition, and its growth from the 17th century. Subsequently, the "disease" declined and eventually disappeared.  After Nature, W. G. Sebald’s first literary work, now translated into English by Michael Hamburger, explores the lives of three men connected by their restless questioning of humankind’s place in the natural world. From the efforts of each, “an order arises, in places beautiful and comforting, though more cruel, too, than the previous state of ignorance.” The first figure is the great German Re-naissance painter Matthias Grünewald. The second is the Enlightenment botanist-explorer Georg Steller, who accompanied Bering to the Arctic. The third is the author himself, who describes his wanderings among landscapes scarred by the wrecked certainties of previous ages.  A giant wooden sardine is carried above the heads of a jostling throng. Realistically carved and highly painted, it is both symbolic and functional, for this is the coffin of the chief sardine fisherman of Teshi. Funerary art has many expressions, but seldom as surprising as among the Ga, the dominant people of the Ghanaian capital Accra and its region. Here, a remarkable contemporary folk art of coffin-building has developed, combining remembrance, respect, humour and celebration. The coffin may take almost any form - onion, cow, fishing boat, car, eagle - reflecting the occupation, status or particular attribute of the deceased. This is a record of a variety of these sculptures. It shows the making of the coffins, the funeral rites, the burial, and explains the history and background of the subject. The main protagonists are introduced: the artist-craftsmen, the mourners, and the central characters whose souls are being sent off in style.  Sideshow banners and freak show culture of the American carnival. |  Charles Willson Peale was not only one of our finest early American painters, but also the founder of the world's first popular museum of natural science and art.Peale's Museum, born of the painter's revolutionary idea that museums should be for everyone—not just for scientists and connoisseurs as had always been the case—was begun in the painter-naturalist's Philadelphia home, and over a seventy-five-year span it grew to include branches in New York City and Baltimore. In its day, Peale's Museum was an institute of learning and science comparable in national prestige to the Smithsonian Institution today.  Steven Shapin argues that science, for all its immense authority and power, is and always has been a human endeavor, subject to human capacities and limits. Put simply, science has never been pure. To be human is to err, and we understand science better when we recognize it as the laborious achievement of fallible, imperfect, and historically situated human beings. |

Morbid Anatomy Museum

Collection Total:

1,253 Items

1,253 Items

Last Updated:

Jan 26, 2016

Jan 26, 2016

Made with Delicious Library

Made with Delicious Library